(1) This is the blessing with which Moses, man of God, blessed the Israelites before he died.

(1) יהוה said to Abram, “Go forth from your native land and from your father’s house to the land that I will show you. (2) I will make of you a great nation, And I will bless you; I will make your name great, And you shall be a blessing.

(3) I will bless those who bless you And curse the one who curses you; And all the families of the earth Shall bless themselves by you.”

(31) Don’t listen to Hezekiah. For thus said the king of Assyria: Make your beracha with me and come out to me so that you may all eat from your vines and your fig trees and drink water from your cisterns...

(25) A 'generous person' enjoys prosperity; One who satisfies others shall themselves be sated.

Berakhot: Blessings

A berakhah (blessing) is a special kind of prayer that is very common in Judaism. Berakhot are recited both as part of the synagogue services and as a response or prerequisite to a wide variety of daily occurrences. Berakhot are easy to recognize: they all start with the word barukh (blessed or praised).

The words barukh and berakhah are both derived from the Hebrew root Bet-Resh-Kaf, meaning "knee," and refer to the practice of showing respect by bending the knee and bowing. There are several places in Jewish liturgy where this gesture is performed, most of them at a time when a berakhah is being recited.

According to Jewish tradition, a person should recite 100 berakhot each day! This is not as difficult as it sounds. Repeating the Shemoneh Esrei three times a day (as all observant Jews do) covers 57 berakhot all by itself, and there are dozens of everyday occurrences that require berakhot.

Who Blesses Whom?

Many English-speaking people find the idea of berakhot very confusing. To them, the word "blessing" seems to imply that the person saying the blessing is conferring some benefit on the person he is speaking to. For example, in Catholic tradition, a person making a confession begins by asking the priest to bless him. Yet in a berakhah, the person saying the blessing is speaking to G-d. How can the creation confer a benefit upon the Creator?

This confusion stems largely from difficulties in the translation. The Hebrew word "barukh" is not a verb describing what we do to G-d; it is an adjective describing G-d as the source of all blessings. When we recite a berakhah, we are not blessing G-d; we are expressing wonder at how blessed G-d is.

Beracha as a noun first appears in Genesis 12:2 precisely as Abraham embarks on his journey to an unknown land. God reassures him, “and you shall be a blessing (וֶהְיֵה בְּרָכָה).” This is an exceedingly important idea in the Torah. God relies on humans to bring blessing into the world. We only have to think of Abraham’s subsequent conversation with God (Gen 18:22-33) in defense of the inhabitants of Sodom and Gomorrah, or Aaron’s priestly blessing (Num 6:22-27), to further illustrate the point. Yet humans, and even blessings, are often sources of anguish and strife. So it is in the next story in which ‘blessing’ appears—that of Jacob and Esau.

Jacob takes the blessing meant for Esau and engenders resentment in his brother (Gen 27: 12, 35, 36, 38, 41). The tension, long-boiling between the brothers, explodes once Isaac prepares to bless only one of his sons. Thus does the story problematize an exclusive blessing given at the expense of another. Many years later, Jacob offers Esau a blessing that leads to reconciliation (Gen 33:11). Blessings are most efficacious when extended to others...

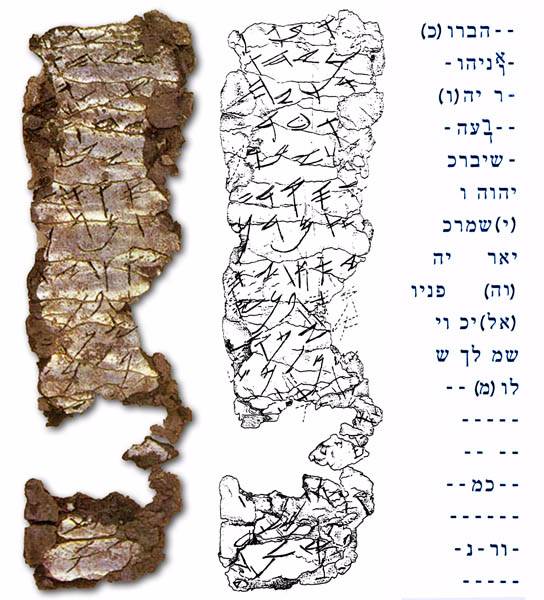

Many of us are familiar with the priestly benediction (birkat hakohanim) from the liturgy, found in Numbers 6:24-26. A sensational archaeological find by Gabriel Barkay in 1979 demonstrates the antiquity of this blessing at least as far back as the 7th century BCE. At the site of Ketef Hinnom (southwest of the Old City of Jerusalem), two tiny silver scrolls with different versions of this birkat hakohanim were discovered, including for example the phrases “May YHWH bless you and guard you; may YHWH make his face shine upon you.”

They were rolled up in a way that indicated that they had been worn by ancient Israelites more than 2600 years ago as amulets. Not only does this archaeological discovery tell us that the benediction was in use at a time before we have any hard evidence for the existence of a written Torah; it also tells us something about how the ancients understood and used the benediction as a form of protection.

Blessings Are a Form of Magic

We think of a blessing as a nice thing to do, whether in response to a sneeze, or as a part of a ritual designed to bestow positive divine attention. In the ancient world though, blessings were often perceived as magical rituals—blessings and curses were understood to have real power to effect change in the human realm.

And Rabbi Yitzchak said: A blessing is found only in an object that is hidden [samui] from the eye. As it is stated: “The Eternal will command blessing upon you in your barns [ba’asamekha]” (Deuteronomy 28:8). The school of Rabbi Yishmael taught: A blessing is found only in an object that is not exposed to the eye, as it is stated: “The Eternal will command His blessing upon you in your barns.”

(23) Speak to Aaron and his children: Thus shall you bless the people of Israel. Say to them: (24) יהוה bless you and protect you!

(25) יהוה deal kindly and graciously with you!

(26) יהוה bestow [divine] favor upon you and grant you peace! (27) Thus they shall link My name with the people of Israel, and I will bless them.

Is this the Kohanim’s blessing to the people? Are they conveying God’s blessing on God’s behalf?

But what exactly is a blessing? It’s easy to speak about when we say them and what precise words we’re supposed to employ. But what does ‘blessing’ itself actually mean?...

Berachah, berech, bereichah, ‘blessing’, ‘knees’, ‘pool of water’: seemingly unlikely partners in English, in Hebrew the three words derive from the same root. They are evidently inter-related, but how? Based on a lecture she had heard, one of the participants demonstrated a literal connection, acting out the sequence of finding a pool of cool water in a desert, falling down on one’s knees and prostrating oneself to drink, before thanking God for this life-giving moment.

Or perhaps the bereichah, the pool, does not refer to not a physical gathering of waters, but rather to the flow of vitality from the invisible reservoir of spirit by which all life is nourished. ‘My soul thirsts for You’, says the Psalmist: ‘Like a deer longing for streams of water, so my whole being longs, God, for You’. I sometimes think it’s the closest we know to the presence of God, when a new alertness, a deeper awareness, quickens us as if from the inside of our own mind...

But blessings are not only from above to below. They also flow between us, and sometimes from below to above. We pondered God’s words to Abraham, ‘Be a blessing’. How is he, how are we supposed to do that? What does ‘be a blessing’ mean? Rachel Remen addresses exactly this question in her beautiful book My grandfather’s Blessings:

When we recognise the spark of God in others, we blow on it with our attention and strengthen it, no matter how deeply it has been buried or for how long. When we bless someone, we touch the unborn goodness in them and wish it well…A blessing is a moment of meeting, a certain kind of relationship in which both people involved remember and acknowledge their true nature and worth, and strengthen what is whole in one another. (p. 5, p. 6).

The final word of the priestly blessing is indeed ‘Shalom’, peace, from a root which means ‘whole’: ‘May God make you whole’.

But what is wholeness, when life so often grinds us down or breaks us apart? ‘Nothing is more whole than the heart which is broken’ said the hasidic master Rebbe Nachman of Breslav, known to have suffered from depressions. It’s what opens us out which makes us most deeply human. Sometimes it’s what seems to break us, which makes the deepest inner wellspring of blessing flow out towards others in recognition and compassion.

Yet that must not make us forget the simple blessings of sights and scents and actions, – for tree blossom, fruits, mountains, and lightning; for being able to open our eyes, get out of bed, put on clothes, – gifts so ordinary we’re in danger of appreciating them only when we no longer have them.

Perhaps the deepest blessing is to be the kind of people who notice our blessings.

Special mention to Va'Era - the Significance of 40

Bereshit Toldot - the Meaning of Lentils

Shemot Tetzaveh - Eternal Light?

Vayikra Tzav - the Holiness of Getting your Hands Dirty

Bamidbar Chukat - the Life and Death of Miriam