(יד) וְהָיָה֩ הַיּ֨וֹם הַזֶּ֤ה לָכֶם֙ לְזִכָּר֔וֹן וְחַגֹּתֶ֥ם אֹת֖וֹ חַ֣ג לַֽיהֹוָ֑ה לְדֹרֹ֣תֵיכֶ֔ם חֻקַּ֥ת עוֹלָ֖ם תְּחׇגֻּֽהוּ׃ (טו) שִׁבְעַ֤ת יָמִים֙ מַצּ֣וֹת תֹּאכֵ֔לוּ אַ֚ךְ בַּיּ֣וֹם הָרִאשׁ֔וֹן תַּשְׁבִּ֥יתוּ שְּׂאֹ֖ר מִבָּתֵּיכֶ֑ם כִּ֣י ׀ כׇּל־אֹכֵ֣ל חָמֵ֗ץ וְנִכְרְתָ֞ה הַנֶּ֤פֶשׁ הַהִוא֙ מִיִּשְׂרָאֵ֔ל מִיּ֥וֹם הָרִאשֹׁ֖ן עַד־י֥וֹם הַשְּׁבִעִֽי׃ (טז) וּבַיּ֤וֹם הָרִאשׁוֹן֙ מִקְרָא־קֹ֔דֶשׁ וּבַיּוֹם֙ הַשְּׁבִיעִ֔י מִקְרָא־קֹ֖דֶשׁ יִהְיֶ֣ה לָכֶ֑ם כׇּל־מְלָאכָה֙ לֹא־יֵעָשֶׂ֣ה בָהֶ֔ם אַ֚ךְ אֲשֶׁ֣ר יֵאָכֵ֣ל לְכׇל־נֶ֔פֶשׁ ה֥וּא לְבַדּ֖וֹ יֵעָשֶׂ֥ה לָכֶֽם׃ (יז) וּשְׁמַרְתֶּם֮ אֶת־הַמַּצּוֹת֒ כִּ֗י בְּעֶ֙צֶם֙ הַיּ֣וֹם הַזֶּ֔ה הוֹצֵ֥אתִי אֶת־צִבְאוֹתֵיכֶ֖ם מֵאֶ֣רֶץ מִצְרָ֑יִם וּשְׁמַרְתֶּ֞ם אֶת־הַיּ֥וֹם הַזֶּ֛ה לְדֹרֹתֵיכֶ֖ם חֻקַּ֥ת עוֹלָֽם׃ (יח) בָּרִאשֹׁ֡ן בְּאַרְבָּעָה֩ עָשָׂ֨ר י֤וֹם לַחֹ֙דֶשׁ֙ בָּעֶ֔רֶב תֹּאכְל֖וּ מַצֹּ֑ת עַ֠ד י֣וֹם הָאֶחָ֧ד וְעֶשְׂרִ֛ים לַחֹ֖דֶשׁ בָּעָֽרֶב׃ (יט) שִׁבְעַ֣ת יָמִ֔ים שְׂאֹ֕ר לֹ֥א יִמָּצֵ֖א בְּבָתֵּיכֶ֑ם כִּ֣י ׀ כׇּל־אֹכֵ֣ל מַחְמֶ֗צֶת וְנִכְרְתָ֞ה הַנֶּ֤פֶשׁ הַהִוא֙ מֵעֲדַ֣ת יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל בַּגֵּ֖ר וּבְאֶזְרַ֥ח הָאָֽרֶץ׃ (כ) כׇּל־מַחְמֶ֖צֶת לֹ֣א תֹאכֵ֑לוּ בְּכֹל֙ מוֹשְׁבֹ֣תֵיכֶ֔ם תֹּאכְל֖וּ מַצּֽוֹת׃ {פ}

(14) This day shall be to you one of remembrance: you shall celebrate it as a festival to יהוה throughout the ages; you shall celebrate it as an institution for all time. (15) Seven days you shall eat unleavened bread; on the very first day you shall remove leaven from your houses, for whoever eats leavened bread from the first day to the seventh day, that person shall be cut off from Israel. (16) You shall celebrate a sacred occasion on the first day, and a sacred occasion on the seventh day; no work at all shall be done on them; only what every person is to eat, that alone may be prepared for you. (17) You shall observe the [Feast of] Unleavened Bread, for on this very day I brought your ranks out of the land of Egypt; you shall observe this day throughout the ages as an institution for all time. (18) In the first month, from the fourteenth day of the month at evening, you shall eat unleavened bread until the twenty-first day of the month at evening. (19) No leaven shall be found in your houses for seven days. For whoever eats what is leavened, that person—whether a stranger or a citizen of the country—shall be cut off from the community of Israel. (20) You shall eat nothing leavened; in all your settlements you shall eat unleavened bread.

(לז) וַיִּסְע֧וּ בְנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֛ל מֵרַעְמְסֵ֖ס סֻכֹּ֑תָה כְּשֵׁשׁ־מֵא֨וֹת אֶ֧לֶף רַגְלִ֛י הַגְּבָרִ֖ים לְבַ֥ד מִטָּֽף׃ (לח) וְגַם־עֵ֥רֶב רַ֖ב עָלָ֣ה אִתָּ֑ם וְצֹ֣אן וּבָקָ֔ר מִקְנֶ֖ה כָּבֵ֥ד מְאֹֽד׃ (לט) וַיֹּאפ֨וּ אֶת־הַבָּצֵ֜ק אֲשֶׁ֨ר הוֹצִ֧יאוּ מִמִּצְרַ֛יִם עֻגֹ֥ת מַצּ֖וֹת כִּ֣י לֹ֣א חָמֵ֑ץ כִּֽי־גֹרְשׁ֣וּ מִמִּצְרַ֗יִם וְלֹ֤א יָֽכְלוּ֙ לְהִתְמַהְמֵ֔הַּ וְגַם־צֵדָ֖ה לֹא־עָשׂ֥וּ לָהֶֽם׃

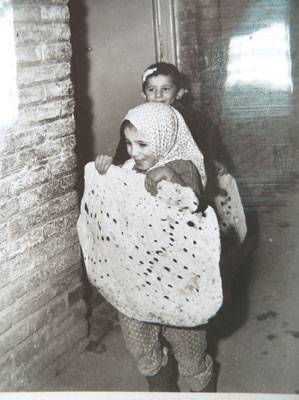

For thousands of years, matza was made by hand. The flour was measured, the water drawn, and a timer was set for eighteen minutes. Then, amid excitement, song, and camaraderie, the dough was kneaded for the sake of the mitzva and rolled into circles. In some communities it was also perforated, so the steam would escape during baking (before the dough swelled into a pita). Finally, the dough was placed in a hot oven.

Each Jewish community made its matza slightly differently. Jews in Arab countries baked soft, thick, laffa-like matzot, slapping the dough onto the oven walls and peeling it off when brown. Iranian matzot were huge, close to a meter in diameter. The Iraqis marked the edges of theirs with one, two, or three “pinches” to show in which order they should be used during the Seder ceremony. The soft matzot of the Yemenites turned stale fast and were therefore baked fresh daily, whereas the thin, crackerlike Ashkenazic matza stayed crunchy all week.

Throughout the other days of the festival, eating matzah is left to one's choice: If one desires, one may eat matzah. If one desires, one may eat rice, millet, roasted seeds, or fruit. Nevertheless, on the night of the fifteenth alone, [eating matzah] is an obligation. Once one eats the size of an olive, he has fulfilled his obligation.

Kaddesh – Blessing over wine.

Urchatz – Washing hands.

Karpas – Green vegetable.

Yachatz – Dividing the matzah.

Magid – Telling the story.

Rochtzah – Washing hands (again).

Motzi – Blessing for matzah.

Matzah – Blessing and eating the matzah.

Maror – Eating bitter herbs.

Korech – The bitter herbs sandwich.

Shulchan Orech – Festive meal.

Tzafun – Afikoman, the hidden dessert.

Barech – Grace after meals.

Hallel – Praising God.

Nirtzah – Concluding songs.

יַחַץ

חותך את המצה האמצעית לשתים, ומצפין את הנתח הגדול לאפיקומן

Break

Split the middle matsah in two, and conceal the larger piece to use it for the afikoman.

מַגִּיד

מגלה את המצות, מגביה את הקערה ואומר בקול רם:

הָא לַחְמָא עַנְיָא דִּי אֲכָלוּ אַבְהָתָנָא בְאַרְעָא דְמִצְרָיִם. כָּל דִכְפִין יֵיתֵי וְיֵיכֹל, כָּל דִצְרִיךְ יֵיתֵי וְיִפְסַח. הָשַּׁתָּא הָכָא, לְשָׁנָה הַבָּאָה בְּאַרְעָא דְיִשְׂרָאֵל. הָשַּׁתָּא עַבְדֵי, לְשָׁנָה הַבָּאָה בְּנֵי חוֹרִין.

The Recitation [of the exodus story]

The leader uncovers the matsot, raises the Seder plate, and says out loud:

This is the bread of destitution that our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt. Anyone who is famished should come and eat, anyone who is in need should come and partake of the Pesach sacrifice. Now we are here, next year we will be in the land of Israel; this year we are slaves, next year we will be free people.

רַבָּן גַּמְלִיאֵל הָיָה אוֹמֵר: כָּל שֶׁלֹּא אָמַר שְׁלשָׁה דְּבָרִים אֵלּוּ בַּפֶּסַח, לא יָצָא יְדֵי חוֹבָתוֹ, וְאֵלּוּ הֵן: פֶּסַח, מַצָּה, וּמָרוֹר...

אוחז המצה בידו ומראה אותה למסובין:

מַצָּה זוֹ שֶׁאָנוֹ אוֹכְלִים, עַל שׁוּם מַה? עַל שׁוּם שֶׁלֹּא הִסְפִּיק בְּצֵקָם שֶׁל אֲבוֹתֵינוּ לְהַחֲמִיץ עַד שֶׁנִּגְלָה עֲלֵיהֶם מֶלֶךְ מַלְכֵי הַמְּלָכִים, הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא, וּגְאָלָם, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: וַיֹּאפוּ אֶת־הַבָּצֵק אֲשֶׁר הוֹצִיאוּ מִמִּצְרַיִם עֻגֹת מַצּוֹּת, כִּי לֹא חָמֵץ, כִּי גֹרְשׁוּ מִמִּצְרַיִם וְלֹא יָכְלוּ לְהִתְמַהְמֵהַּ, וְגַם צֵדָה לֹא עָשׂוּ לָהֶם.

Rabban Gamliel was accustomed to say, Anyone who has not said these three things on Pesach has not fulfilled his obligation, and these are them: the Pesach sacrifice, matsa and marror...

He holds the matsa in his hand and shows it to the others there.

This matsa that we are eating, for the sake of what [is it]? For the sake [to commemorate] that our ancestors' dough was not yet able to rise, before the King of the kings of kings, the Holy One, blessed be He, revealed [Himself] to them and redeemed them, as it is stated (Exodus 12:39); "And they baked the dough which they brought out of Egypt into matsa cakes, since it did not rise; because they were expelled from Egypt, and could not tarry, neither had they made for themselves provisions."

מוֹצִיא מַצָּה

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה', אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם הַמּוֹצִיא לֶחֶם מִן הָאָרֶץ.

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה', אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם, אֲשֶׁר קִדְּשָׁנוּ בְּמִצְוֹתָיו וְצִוָּנוּ עַל אֲכִילַת מַצָּה.

Motsi Matsa

Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the Universe, who brings forth bread from the ground.

Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the Universe, who has sanctified us with His commandments and has commanded us on the eating of matsa.

כּוֹרֵךְ

כל אחד מהמסבים לוקח כזית מן המצה השְלישית עם כזית מרור, כורכים יחד, אוכלים בהסבה ובלי ברכה. לפני אכלו אומר.

זֵכֶר לְמִקְדָּשׁ כְּהִלֵּל. כֵּן עָשָׂה הִלֵּל בִּזְמַן שֶׁבֵּית הַמִּקְדָּשׁ הָיָה קַיָּם:

הָיָה כּוֹרֵךְ מַצָּה וּמָרוֹר וְאוֹכֵל בְּיַחַד, לְקַיֵּם מַה שֶּׁנֶּאֱמַר: עַל מַצּוֹת וּמְרוׂרִים יֹאכְלֻהוּ.

Wrap

All present should take a kazayit from the third whole matsa with a kazayit of marror, wrap them together and eat them while reclining and without saying a blessing. Before he eats it, he should say:

In memory of the Temple according to Hillel. This is what Hillel would do when the Temple existed:

He would wrap the matsa and marror and eat them together, in order to fulfill what is stated, (Numbers 9:11): "You should eat it upon matsot and marrorim."

צָפוּן

אחר גמר הסעודה לוקח כל אחד מהמסבים כזית מהמצה שהייתה צפונה לאפיקומן ואוכל ממנה כזית בהסבה. וצריך לאוכלה קודם חצות הלילה.

לפני אכילת האפיקומן יאמר: זֵכֶר לְקָרְבָּן פֶּסַח הָנֶאֱכַל עַל הָשוֹׁבַע.

The Concealed [Matsa]

After the end of the meal, all those present take a kazayit from the matsa, that was concealed for the afikoman, and eat a kazayit from it while reclining.

Before eating the afikoman, he should say: "In memory of the Pesach sacrifice that was eaten upon being satiated."

Matzah features repeatedly in the Seder. Close to the opening, it is described as Halachma Anya, ‘the bread of poverty’ our ancestors ate in Egypt. It was probably originally at this point that the door would be opened, to welcome in the hungry and the poor. In No Time For Tears, the touching account of his East End childhood in the 1930’s, Sidney Bloch recalls how his parents never locked the front door and always laid an extra place at the table.

Shmuel Hanagid (993 – 1056) has a simple culinary explanation:

Some say bread of poverty means, literally, the bread of the poor – because poor people, in the severity of their destitution, will take some floor, knead it and bake it into unleavened bread which they eat immediately…

The middle matzah is now broken, to represent how, as the Talmud, explains a poor person never has a complete loaf, only a torn half. Eli Wiesel provides a frighteningly poignant insight: the person in terror of starvation, who never knows from where the next miniscule, inadequate meal will come, doesn’t dare to eat a whole piece of bread, but hides half fearfully away.

The broken half is held up repeatedly during as we recount the story of slavery, remembering the suffering of our forebears in Egypt, and others who once were, and all who still today are, the slaves of hunger and exploitation.

Close to the end of the narrative, the very same matzah becomes the bread our ancestors take with them on their journey of freedom. It turns into the bread of hope, or, as the Zohar names it, the food of faith, mechla de’meheimanuta, and lachma de’asuta, the bread of healing. This health is moral rather than physical: it is the healing-power present in the society where those who are replete do not forget those who are hungry and use their freedom to set others free.

Matzah thus makes the journey from slavery to freedom alongside us.

There are still two further features which connect matzah with liberty. In a creative word play, the Talmud (Pesachim 115b – 116a) links lechem oni, the bread of poverty, with the verb oneh, ‘answer’. Matzah is the bread ‘over which matters are answered’. It is the food of discourse, of questions and discussions. Freedom of speech is an essential, primary freedom. In a totalitarian regime, in a country where people know that their every word may be overheard and reported, even in a household dominated by domestic tyranny, no one dares to speak out openly. ‘Bread over which matters are answered’, over which significant issues are challenged, debated and considered from a multitude of angles, is the bread of freedom indeed.

The Talmud takes this one step further. Baking matzah requires team-work. This is depicted clearly in numerous Haggadah illustrations: one person is measuring the flour, others are mixing the dough and yet others rolling it out, while further figures make the holes, put the pastry in the oven, take it out and place the finished matzah in baskets.

The right to collaboration is a form of liberty. The freedom to meet in open fellowship and association has been banned or controlled by every totalitarian regime. Nazi plans for the annexation of western Poland after their swift victory in 1939 included making it illegal for Poles to gather together, even in sports clubs or cafes. (Jews were simply deported).

Matzah, in contrast, celebrates and embodies the freedom of friendship and co-operation.

Matso is used ceremonially four times. We start by breaking the middle matso and hiding the larger half. Ha lachma anya - this is “the bread of affliction” our ancestors ate in Egypt. Here matso represents the food of lowest status. Slaves don’t get a whole loaf; they're lucky to get the smaller half.

Next is the matso of Rabban Gamliel - the bread we ate on leaving Egypt, in haste, no time to rise to form nice loaves. Slaves en route to freedom, in transition, but not yet home free.

Next is Korech, Hillel's sandwich, zecher l'mikdash, to recall the Temple in Jerusalem, when we were free and sovereign in our own land. Here matso represents not the story of Egypt itself, but the commemoration of that story by the Jewish people at a high point in our history, one which the creators of the Haggadah could only long for.

And finally matso appears for dessert in Tsafon, late at night, reminding us of the Korban Pesach with which the festive meal in Temple times concluded, hinting at the redemption we hope for in the future. Matso, which began the evening as the sign of our lowest moment, slavery in Egypt, has been gradually transformed, step by step through the Seder ceremony, into the symbol of our highest hopes.