He said:

You will lose your hands.

I said:

What use are my hands now?

He said:

You will lose your lips.

I said:

What use are my lips now?

He said:

Your eyes will be dry lakes.

I said:

I know the book by heart.

Edmund Jabes

These words are written by Egyptian Jewish poet Edmond Jabés. Involuntarily relocated to France in 1956, after the Suez crisis between Israel and Egypt, Jabés knew firsthand what the book of Devarim seeks to establish – that a book can become a site of exile, longing, and identity. That poetry offers pathways into our humanity, and that the written word can be a place of home.

Excerpted from Rabbi Monica Gomery, Stop Making Sense

https://hebrewcollege.edu/blog/stop-making-sense/

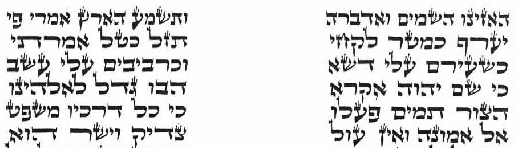

(יט) וְעַתָּ֗ה כִּתְב֤וּ לָכֶם֙ אֶת־הַשִּׁירָ֣ה הַזֹּ֔את וְלַמְּדָ֥הּ אֶת־בְּנֵי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל שִׂימָ֣הּ בְּפִיהֶ֑ם לְמַ֨עַן תִּהְיֶה־לִּ֜י הַשִּׁירָ֥ה הַזֹּ֛את לְעֵ֖ד בִּבְנֵ֥י יִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃

(19) Therefore, write down this song and teach it to the people of Israel; put it in their mouths, in order that this poem may be My witness against the people of Israel.

And set the divisions of humanity,

[God] fixed the boundaries of peoples

In relation to Israel’s numbers.

(9) For יהוה’s portion is this people;

Jacob, God’s own allotment.

(י) יִמְצָאֵ֙הוּ֙ בְּאֶ֣רֶץ מִדְבָּ֔ר וּבְתֹ֖הוּ יְלֵ֣ל יְשִׁמֹ֑ן יְסֹבְבֶ֙נְהוּ֙ יְב֣וֹנְנֵ֔הוּ יִצְּרֶ֖נְהוּ כְּאִישׁ֥וֹן עֵינֽוֹ׃ (יא) כְּנֶ֙שֶׁר֙ יָעִ֣יר קִנּ֔וֹ עַל־גּוֹזָלָ֖יו יְרַחֵ֑ף יִפְרֹ֤שׂ כְּנָפָיו֙ יִקָּחֵ֔הוּ יִשָּׂאֵ֖הוּ עַל־אֶבְרָתֽוֹ׃ (יב) יְהֹוָ֖ה בָּדָ֣ד יַנְחֶ֑נּוּ וְאֵ֥ין עִמּ֖וֹ אֵ֥ל נֵכָֽר׃ (יג) יַרְכִּבֵ֙הוּ֙ עַל־[בָּ֣מֳתֵי] (במותי) אָ֔רֶץ וַיֹּאכַ֖ל תְּנוּבֹ֣ת שָׂדָ֑י וַיֵּנִקֵ֤הֽוּ דְבַשׁ֙ מִסֶּ֔לַע וְשֶׁ֖מֶן מֵחַלְמִ֥ישׁ צֽוּר׃

In an empty howling waste.

[God] engirded them, watched over them,

Guarded them as the pupil of God’s eye.

(11) Like an eagle who rouses its nestlings,

Gliding down to its young,

So did [God] spread wings and take them,

Bear them along on pinions;

(12) יהוה alone did guide them,

No alien god alongside.

(13) [God] set them atop the highlands,

To feast on the yield of the earth;

Nursing them with honey from the crag,

And oil from the flinty rock,

(א) בְּרֵאשִׁ֖ית בָּרָ֣א אֱלֹהִ֑ים אֵ֥ת הַשָּׁמַ֖יִם וְאֵ֥ת הָאָֽרֶץ׃ (ב) וְהָאָ֗רֶץ הָיְתָ֥ה תֹ֙הוּ֙ וָבֹ֔הוּ וְחֹ֖שֶׁךְ עַל־פְּנֵ֣י תְה֑וֹם וְר֣וּחַ אֱלֹהִ֔ים מְרַחֶ֖פֶת עַל־פְּנֵ֥י הַמָּֽיִם׃

The poetry works. Words, like rain, can be soft like morning dew that gently offers itself the earth's vegetation, tending to its growth. Or words can be like torrential rains that destroy and uproot.

Just as plants need different rains to nurture their growth, people need different words as well. There are times when gentle speech is required and there are times when harsh words of rebuke are needed. Know well the kind of words needed and speak them well, warns our teacher. All words, when properly delivered, are of the living God.

― Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

Is to be in the dream of another

To feel a light pull, like reins tugging. To feel

a heavy pull, like chains.

Yehudah Amichai, from The Fist Too Was Once an Open Hand and Fingers, 1989

אלים מתחלפים, התפילות נשארות לעד

1 רָאִיתִי בָּרְחוֹב, בְעֶרֶב קַיִץ,

רָאִיתִי אִֹשָה ֹשֶכָּתְבָה מִלִים

עַל נְָיר פָרוּשֹ עַל דֶלֶת עֵץ נְעוּלָה,

וְקִפְּלָה וְשָֹמָה בֵּין דֶּלֶת לַמְּזוּזָה וְהָלְכָה לָהּ.

וְלֹא רָאִיתִי אֶת פָּנֶיהָ וְלֹא אֶת פְּנֵי הָאִיֹש

ֹשֶיִּקְרָא אֶת הַכָּתוּב

וְלֹא רָאִיתִי אֶת הַמִלִים.

עַל ֹשֻלְחָנִי מֻנַחַת אֶבֶן ֹשֶכּתוּב עָלֶיָ "אָמֵן",

ֹשֶבֶר מַצֵּבָה, ֹשְאֵרִית מִבֵּית קְבָרוֹת יְהוּדִי

ֹשֶנֶּחֱרַב לִפְנֵי כְּאֶלֶף ֹשָנִים, בָּעִיר ֹשֶבָּהּ נוֹלַדְתִי.

מִלָּה אַחַת "אָמֵן" חֲרוּתָה עָמֹק בָּאֶבֶן

אֵָמֵן קָֹשֶה וְסוֹפִי עַל כָּל ֹשֶהָיָה וְלֹא יָֹשוּב,

אָמֵן רַךְ וּמְזַמֵר כְּמוֹ בִּתְפִילָה,

אָמֵן וְאָמֵן, וְכֵן יְהִי רָצון.

מַצֵּבוֹת נֹשְבָּרוֹת, מִלִים חוֹלְפוֹת, מִלִים נִֹשכָּחוֹתּ,

שְֹפָתַיִם ֹשֶאָמְרוּ אוֹתן הָפְכוּ עָפָר,

שָֹפוֹת מֵתוֹת כִּבְנֵי אָדָם,

שָֹפוֹת אֲחֵרוֹת קָמוֹת לִתְחִיָה,

אֵלִים בַֹשָמִַיִם מִֹשְתַּנִים, אֵלִים מִתְחַלְּפִים,

הַתְּפִילוֹת נִֹשְאָרוֹת לָעַד

I

In the street on a summer evening, I saw a woman writing

on a piece of paper spread out against a locked wooden door.

She folded it, tucked it between door and doorpost, and went on her way.

And I didn’t see her face, nor the face of the man

who would read what she had written

and I didn’t see the words.

On my desk lies a stone with the word “Amen” on it,

a fragment of a tombstone, a remnant from a Jewish graveyard

destroyed a thousand years ago in the town where I was born.

One word, “Amen,” carved deep into the stone,

a final hard amen for all that was and never will return,

a soft singing amen, as in prayer:

Amen and amen, may it come to pass.

Tombstones crumble, they say, words tumble, words fade away,

the tongues that spoke them turn to dust,

languages die as people do,

some languages rise again,

gods changes up in heaven, gods get replaced

prayers are here to stay.